Cycling between two empires

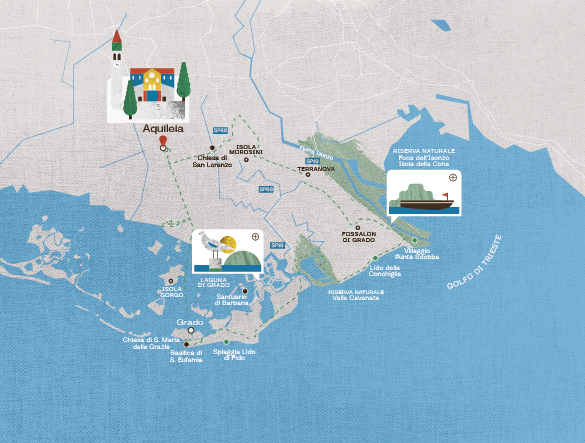

The beautiful cycle path, which starts just behind that magnificent layered monument of the Basilica of Aquileia, crosses the grounds of an Imperial Regia railway, which brought Austrian nobles and bourgeois on holiday to Grado. Apart from contemplating the landscape, this journey also involves the traveller’s mind, knowledge, and emotions. Looking back in time, beyond the current orderly geometry of the fields, you can imagine being in the 9th century.

The forest dating back to the year 800 had covered over the Roman centuriation and, among oaks, ash trees and alders, which today are no longer there, once you could have met none other than Charlemagne hunting together with his knights. In fact, with the arrival of the Longobards, in 568, a historical fracture was produced that decreed the existence of two very different worlds, leaving the signs of this temporal and cultural fault in the architecture. In fact, to make a long story short, the Knights of the North, Longobards, Franks and then the Habsburgs all stopped in front of the insidious lagoon of Grado. They had no seafaring knowledge, and, as Grado was just five kilometres from the coast, they ended up sailing into Venetian and Byzantine waters: the Eagle of the Northern Empire opposite the Lion of San Marco and the Eastern Empire. Therefore, the two Emperors travelling on this time train were those of Constantinople and the Empire. But this is just a made-up story in order to understand why in Aquileia there are still austere palaces with Austrian names, and in Grado, which you will encounter shortly, it is possible to get lost in a maze of streets with evident Venetian DNA. In short, history has become interwoven in urban planning and architecture. Four kilometres from the start, the GPS track bends to the right and leads along a beautiful white road. At the end of which the outline of a pine forest can be seen. It is a fascinating place, full of history, but above all legend, The pine forest and the church of San Marco stand on one of the few fossil dunes, anchored by the vegetation preventing its disintegration and surviving the reclamation. It already existed in Roman times, as evidenced by archaeological finds. The view of the lagoon is breath-taking, especially at sunset. The 18th-century church and the small cemetery instil a sense of peace. As we were saying, history and legend have it that the Christian Jew Saint Mark, from Alexandria in Egypt, landed here to evangelize the territory. Three and a half kilometres is the length of the detour from the cycle path, but you can always continue straight towards Grado.

It is almost like riding on the water, with the Barbana sanctuary on the left and its dome reflected in the lagoon. If the new part of Grado has little to show from an architectural point of view, the historic centre is full of charm, with its informal architecture and streets, with sacred images and devotional altars at the crossroads. And then there are the porticoes, the squares with ancient trees and, of course, restaurants and taverns for every taste. But here too, there are two excellences: the Basilica of Sant’Eufemia – coincidentally a Byzantine martyr – and the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, with its precious Greek marble. Both are early Christian, dating back to the 6th century. Make sure you don’t miss them.

Leaving Grado, a cycle path leads you towards the Primero bridge, which crosses one of the entrance canals of the lagoon. After the bridge, the cycle path bends to the right, along the naturalist area of the Cavanata Valley. You are now in the Vittoria reclamation area, where, in the 19th century, there was an area of marshes and fishermen’s huts, which was drained in 1933. Today, thanks to a reclamation embankment that prevents the sea from flooding the crops, you find yourself cycling in an elevated and privileged position: on the right, there is a superb view of Istria and the Gulf of Trieste (which is clearly visible, like a nativity scene far below the Karst), and on the left the fields, all below sea level. You reach Caneo, an expanse of marsh reeds, which turn golden in summer and shudder in the wind like the fur of a feline in the winter. The tiny village of Punta Sdobba, overlooking the river, five hundred metres from the Caneo restaurant, is enchanting: small houses, a tiny still active port, and a view of the blue-turquoise mouth of the Isonzo river, the Karst and Trieste, which are gems to be enjoyed in silence. After following the road that runs along the Isonzato embankment, a tributary to the right of the Isonzo, turn right onto the SP19. There are two alternatives: either continue for two km over the Isonzo bridge and then turn right until reaching Isola della Cona, a protected natural area (another ten kilometres), or turn left after five hundred metres to reach Isola Morosini, “flava di paschi e cesia di stagni”, as D’Annunzio, who was fascinated by the area defined it. It is a quiet village, with many abandoned houses, spring waters and nothing spectacular except its quiet and beautiful sycamore trees. It is less than five kilometres of quiet roads from here to San Lorenzo Fiumicello. In the 16th-century church, another minor treasure is an austere work depicting the Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Carlo da Carona, 15th century: recommended only for true enthusiasts.

You will likely arrive at sunset when the last rays give the Basilica warm and pinkish hues. And why not enjoy a glass of good Friuli wine, sitting in the bar opposite, reliving the day that took you through Empires, lagoons, sea and History?